Introduction to Docker

Overview

Teaching: 20 min

Exercises: 0 minQuestions

What is Docker?

What is a

Dockerfile?What is a container image?

What is a container?

What is a container registry and why should I use a registry as part of my research workflow?

Why should I use Docker containers as part of my reseach workflow?

Objectives

Explain how containers can be used to enhance portability and reproducibility of research workflows.

Explain the difference between a container image and a container.

Explain how a container differs from a virtual machine.

Understand how container registries, such as DockerHub, can be used to automate research workflows.

What is Docker?

Docker is an open source platform for developing, deploying, and running applications inside standardized units of software called containers. Docker is essentially synonymous with the process of containerization. If you’re a current or aspiring (research) software engineer or (data) scientist, Docker is in your future.

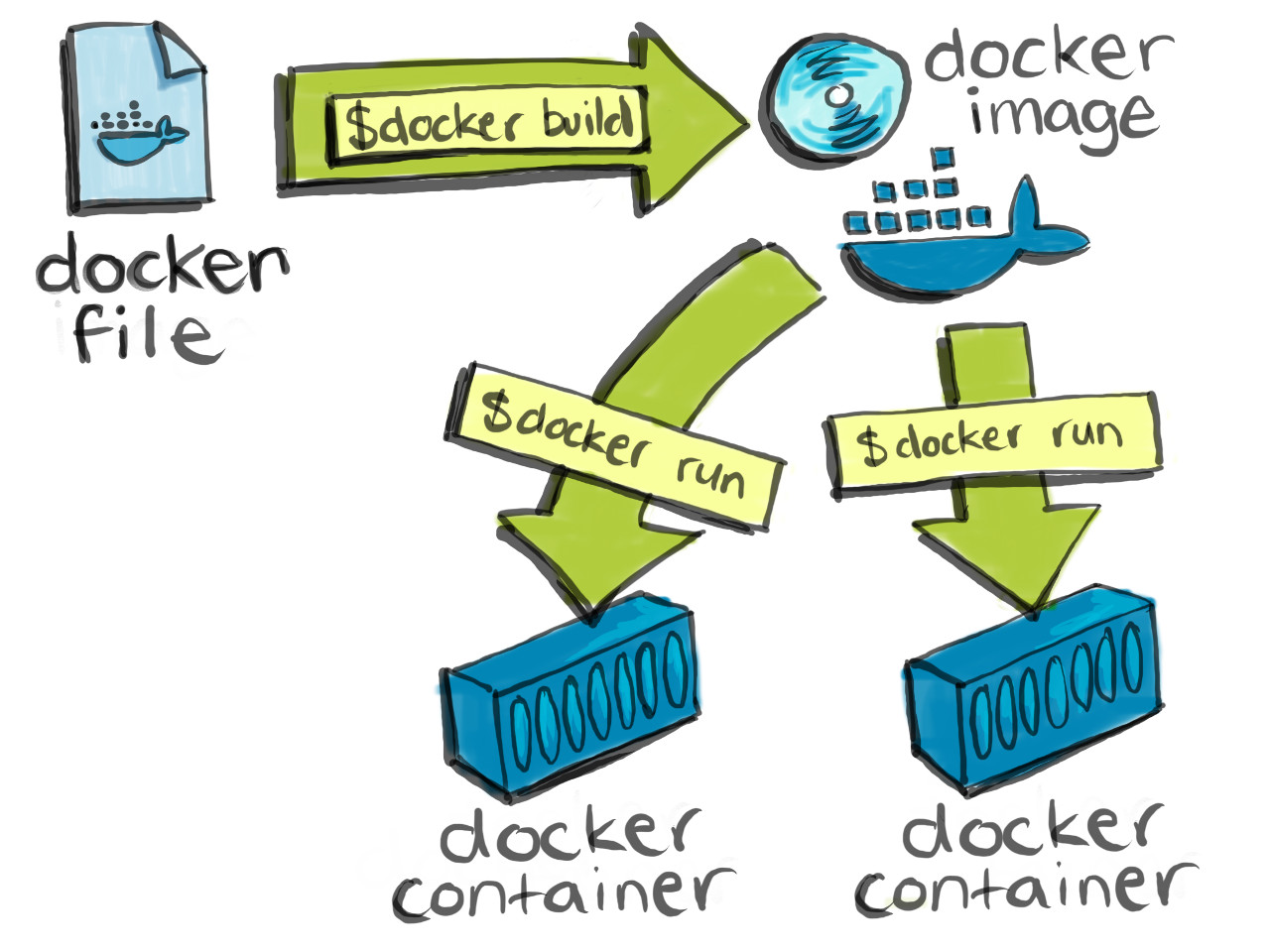

What is a Dockerfile?

A Dockerfile is a text document that contains all the commands a user could call on the command

line to assemble an Docker container image. Each instruction in a Dockerfile adds a new “layer”

to the container image, with layers representing a portion of the images file system that either

adds to or replaces the layer below it. We will be covering Dockerfiles in quite a bit of detail in a later episode of this lesson where you will learn when and how to write your own Dockerfile.

Some example Dockerfiles

Here is an example of a

Dockerfilefrom the Rocker project.FROM rocker/rstudio:3.6.0 RUN apt-get update -qq && apt-get -y --no-install-recommends install \ libxml2-dev \ libcairo2-dev \ libsqlite3-dev \ libmariadbd-dev \ libmariadb-client-lgpl-dev \ libpq-dev \ libssh2-1-dev \ unixodbc-dev \ libsasl2-dev \ && install2.r --error \ --deps TRUE \ tidyverse \ dplyr \ devtools \ formatR \ remotes \ selectr \ caTools \ BiocManagerThis

Dockerfilehas two layers and describes how to install the popular tidyverse libraries (and their required dependencies!) on top of a Docker container image containing version 3.6 of RStudio.Here is another, more involved

Dockerfileprepared by the kind folks at the Jupyter project.# Copyright (c) Jupyter Development Team. # Distributed under the terms of the Modified BSD License. ARG BASE_CONTAINER=jupyter/scipy-notebook FROM $BASE_CONTAINER LABEL maintainer="Jupyter Project <jupyter@googlegroups.com>" # Set when building on Travis so that certain long-running build steps can # be skipped to shorten build time. ARG TEST_ONLY_BUILD USER root # R pre-requisites RUN apt-get update && \ apt-get install -y --no-install-recommends \ fonts-dejavu \ gfortran \ gcc && \ rm -rf /var/lib/apt/lists/* # Julia dependencies # install Julia packages in /opt/julia instead of $HOME ENV JULIA_DEPOT_PATH=/opt/julia ENV JULIA_PKGDIR=/opt/julia ENV JULIA_VERSION=1.1.0 RUN mkdir /opt/julia-${JULIA_VERSION} && \ cd /tmp && \ wget -q https://julialang-s3.julialang.org/bin/linux/x64/`echo ${JULIA_VERSION} | cut -d. -f 1,2`/julia-${JULIA_VERSION}-linux-x86_64.tar.gz && \ echo "80cfd013e526b5145ec3254920afd89bb459f1db7a2a3f21849125af20c05471 *julia-${JULIA_VERSION}-linux-x86_64.tar.gz" | sha256sum -c - && \ tar xzf julia-${JULIA_VERSION}-linux-x86_64.tar.gz -C /opt/julia-${JULIA_VERSION} --strip-components=1 && \ rm /tmp/julia-${JULIA_VERSION}-linux-x86_64.tar.gz RUN ln -fs /opt/julia-*/bin/julia /usr/local/bin/julia # Show Julia where conda libraries are \ RUN mkdir /etc/julia && \ echo "push!(Libdl.DL_LOAD_PATH, \"$CONDA_DIR/lib\")" >> /etc/julia/juliarc.jl && \ # Create JULIA_PKGDIR \ mkdir $JULIA_PKGDIR && \ chown $NB_USER $JULIA_PKGDIR && \ fix-permissions $JULIA_PKGDIR USER $NB_UID # R packages including IRKernel which gets installed globally. RUN conda install --quiet --yes \ 'rpy2=2.9*' \ 'r-base=3.5.1' \ 'r-irkernel=0.8*' \ 'r-plyr=1.8*' \ 'r-devtools=1.13*' \ 'r-tidyverse=1.2*' \ 'r-shiny=1.2*' \ 'r-rmarkdown=1.11*' \ 'r-forecast=8.2*' \ 'r-rsqlite=2.1*' \ 'r-reshape2=1.4*' \ 'r-nycflights13=1.0*' \ 'r-caret=6.0*' \ 'r-rcurl=1.95*' \ 'r-crayon=1.3*' \ 'r-randomforest=4.6*' \ 'r-htmltools=0.3*' \ 'r-sparklyr=0.9*' \ 'r-htmlwidgets=1.2*' \ 'r-hexbin=1.27*' && \ conda clean --all -f -y && \ fix-permissions $CONDA_DIR && \ fix-permissions /home/$NB_USER # Add Julia packages. Only add HDF5 if this is not a test-only build since # it takes roughly half the entire build time of all of the images on Travis # to add this one package and often causes Travis to timeout. # # Install IJulia as jovyan and then move the kernelspec out # to the system share location. Avoids problems with runtime UID change not # taking effect properly on the .local folder in the jovyan home dir. RUN julia -e 'import Pkg; Pkg.update()' && \ (test $TEST_ONLY_BUILD || julia -e 'import Pkg; Pkg.add("HDF5")') && \ julia -e "using Pkg; pkg\"add Gadfly RDatasets IJulia InstantiateFromURL\"; pkg\"precompile\"" && \ # move kernelspec out of home \ mv $HOME/.local/share/jupyter/kernels/julia* $CONDA_DIR/share/jupyter/kernels/ && \ chmod -R go+rx $CONDA_DIR/share/jupyter && \ rm -rf $HOME/.local && \ fix-permissions $JULIA_PKGDIR $CONDA_DIR/share/jupyterThis

Dockerfilehas 15 layers (if I have counted correctly!) and describes how to install version 3.5.1 of the R programming language, a bunch of popular R data science libraries, and version 1.1 of the Julia programming language on top of thejupyter/scipy-notebookcontainer image (which itself contains Python 3 and a bunch of widely used Python data science packages).

What is a container image?

A Docker container image is a lightweight, standalone, executable package of software that includes everything needed to run an application: code, runtime, system tools, system libraries and settings.

- Each Docker container image is built from a set of instructions written in a

Dockerfile. - Images define both what you want your packaged application and its dependencies to look like and what processes to run when it’s launched.

We will be discussing Docker container images at length in a later episode. In particular we will cover the following.

- Where to find existing container images for your research project?

- When and how to build your own container images?

- How to share your container images with your peers and colleagues?

What is a container?

A container is a standard unit of software that packages up your code and all its dependencies so the application runs quickly and reliably from one computing environment to another. A container wraps an application’s software into an invisible box with everything the application needs to run. Docker containers are built from Docker container images. Since container images are read-only, Docker adds a read-write file system over the immutable file system of the container image in order to create a container.

What is the difference between a container image and a container?

A container image is an immutable master template containing all the libraries and code that your research application needs to run bundled together. Once created a container image can be used as a “blueprint” to individual containers that are exact copies of one another.

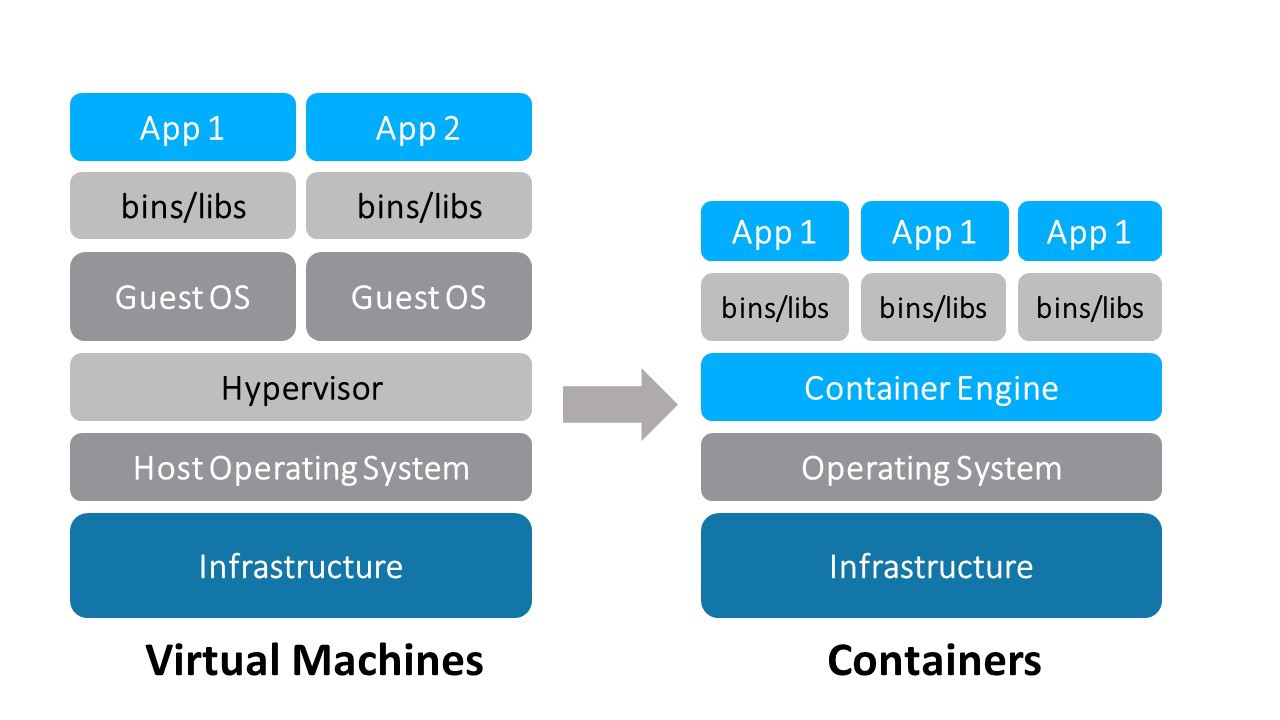

Containers vs. Virtual Machines (VMs)

VMs are the precursors to Docker containers. Like Docker containers, VMs machines are a technology for isolating an application and its dependencies from other applications and dependencies running on the same host OS. However, Docker containers are have several benefits over VMs.

- Containers require fewer resources from the host OS than do VMs

- Containers are very portable relative to VMs

- Containers are faster to spin up than VMs

For more details on the similarities and differences between containers and VMs have a read through this article on Medium.

Containers and VMs are not mutually exclusive

Public cloud providers such as AWS, GCP, and Azure almost always combine VMs and containers.

What is a container registry?

If you want other people to be able to make containers from your image, you need to store them in a container registry. A container registry is a remote location where container images are stored. In the same way in which you push source code changes from you local Git repository to a remote repository on GitHub and pull changes from remote GitHub repositories to your local Git repository, youwill push container images to a registry and pull images from a registry. You can host your own registry or use a provider’s registry. For example, AWS and Google Cloud have registries. Docker Hub is the largest registry and the default.

Putting it all together

Why should I use Docker containers as part of my research workflow?

Containers help improve reproducibility and scalability of software development and (data) science workflows. Containerized software will always run the same, regardless of the infrastructure. Containers isolate software from its environment and ensure that it works uniformly despite differences between, for example, the host operating system on you local machine and the host operating system on a remote cluster.

Motivating examples using Jupyter-Stacks and Rocker

Objective is to show learners how I use Docker as part of my develoment workflow to produce reproducible data science pipelines.

Where do we go from here?

Now that we have had an overview of the Docker conceptual landscape, we are going to see some examples of how Docker is enabling innovation in tools that are bringing substantial value to the scientific research community.

Key Points

Docker is a platform for developing, deplying, and running applications inside containers.

Containers help improve the portability, reproducibility, and scalability of software engineering and (data) science workflows.

A container image is a ‘blueprint’ that is used to create standardized units of software called containers.

Publishing your container image to a container registry allows other researchers to create containers from your image and reproduce your results or to build upon your image in order to extend your results.